The Big Bad Congress: The Stain of Fujimori’s Constitution on Peru’s Politics

Although I visited Peru nearly six years ago, Lima’s vibrancy remains vivid in my memory: the hundreds of hair salons stretching for endless blocks; the wafts of oregano and salt-bathed chicken steaming out of restaurant vents and drifting onto the sidewalk; the Spanish-style apartment buildings painted in aged beige and draped with plants that dangle over bronze railings. This beauty, however, is not the focus of my blog; instead, it is the messiness of Peru’s politics. It is the perpetual impeachments, elections, dismal approval ratings, and, above all, congressional dominance that I seek to explore in my writing. I want to understand how these two truths coexist: how a nation with such a rich aesthetic can, simultaneously, be so broken politically.

In the past seven years, Peru has cycled through six presidents. From accusing of Martín Vizcarra of “moral incapacity” after he pushed referendums to reduce Congressional lawmaking authority, to Manuel Merino’s five-day presidency that same year—installed by Congress but ended by massive public backlash—to Congress’s sabotage of more than eighty of Pedro Castillo’s cabinet appointments in 2021, Congressional abuse of power has been the through line of Peru’s political instability. As political scientist Guillermo O’Donnell put it, the Peruvian Congress “acts as a delegative legislature…the branch governs unchecked.” The word “delegate” means to entrust authority to someone who represents the people, yet it also carries an echo of something monarchical—a power elevated above others, almost sovereign. “Legislature” refers to the body that creates laws for the public and is therefore expected to safeguard the people’s interests. In Peru, however, the opposite has occurred. Congress, meant to represent the majority, empowers itself—even at the expense of half a dozen presidents. It rules as a king would his vassals, unrestrained and fully in control.

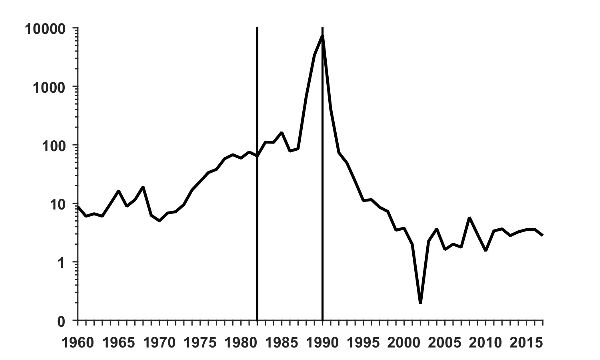

To comprehend how Peru’s Congress ended up with so much power, one must first understand the 1992 self-coup and the subsequent changes made in the constitution. Peru, during the early 90s, faced the dual threats of communist insurgencies and economic collapse. According to a UN Refugee Agency report, foremost among these movements was the Communist Party of Peru, a guerrilla army that sought to turn Peru into a “worker-peasant state.” By 1992, that vision grew slowly into reality, with the group controlling about 40 percent of the country. At the same time, Peru’s debt and inflation grew exponentially: one billion dollars owed to the United States and a 1.2 million percent hyperinflation by 1990. The crisis turned so sour that, at its worst point in 1992, 200 children died per day from malnutrition.

It makes sense, then, why President Fujimori—elected in 1990—pointed his legislative focus toward resolving these twin crises. On the security front, he introduced bills that broadened who could be classified and prosecuted as a terrorist—communist insurgents—and extended how long suspected militants could be detained. On the economic front, he pushed for laws that eliminated tariffs and subsidies, aiming to fold Peru back into the international financial system and lure foreign investment. The problem, however, was that Congress refused to support either agenda. Legislators argued that Fujimori’s expanded definition of terrorism was so broad it could apply to political opponents and would give the military near-unchecked authority, threatening liberties such as freedom of expression. Furthermore, they also feared that suddenly removing economic protections would, rather than shock the country back into stability, tip it deeper into crisis.

Fujimori’s response? On April 5, 1992, he took to television, announcing that, out of an obligation to the well-being of the Peruvian nation, he could no longer tolerate Congress’s obstruction. In the speech, Fujimori declared, “If the country is not rebuilt now—if the foundations of national development are not laid—there is no possible guarantee for the [stability] of Peruvians as a civilized collective or as a State.” The irony here is that rather than rebuilding the foundations of government—rebuilding meaning to work with what exists and restore it—Fujimori’s version of reconstruction meant dissolving, wholly eliminating, what structurally kept Peru intact: Congress and the constitution. Moreover, Fujimori’s “rebuilding” served his own interests far more than the nation’s, for in the hours after his speech, his soldiers seized control of Lima, occupied news stations, and arrested opposition leaders—those who had constrained or criticized his decision making, his own version of “well-being.” As we will see, this façade of acting for the Peruvian people while consolidating personal power becomes even clearer in the way he toyed with the constitution and did not consider its legacy on Peru’s future. Rather than stabilizing the country, he created amendments that ultimately unraveled its political system, undermining the very idea of a “civilized collective,” and leaving the nation without the institutional structure needed to hold itself together.

This was the principal mistake that Fujimori made when he rewrote the constitution: designing it for himself—a strongman president operating in a weak institutional environment, never imagining that once the strongman disappeared, a singular branch of government—Congress—armed with expansive constitutional powers would have no counterweight. How could such an imbalance take root? How could the very part of the government he so despised gain so much power?

In the wake of the coup, Fujimori confronted immediate international backlash for dismantling Peru’s democracy. A 1992 UPI report notes that the IMF suspended $222 million in loans, while, as Ambassador Luigi Einaudi told the OAS Permanent Council, that the U.S. would withhold $275 million—$193 million in economic aid and $43.5 million in anti-narcotics assistance. Because Fujimori’s entire economic strategy depended on reentering global markets and securing foreign investment, and because his legitimacy hinged on defeating the communist insurgency, he needed a constitution that appeared democratic. He needed to counterbalance his own dominance, so he chose to give Congress equivalent authority.

Thus, the 1993 Constitution declared:

(1) “The Legislative Power resides in the Congress of the Republic, which consists of a single chamber.”

(2) Congress “makes effective the political responsibility of the Council of Ministers by means of a vote of no confidence or the rejection of the question of confidence.”

(3) The presidency “vacates for permanent moral or physical incapacity,” a status declared solely by Congress.

At first glance, this framework seems to give Congress an extraordinary concentration of power, but in 1993, it did not. Fujimori still commanded the armed forces, the national police, and the intelligence services. His emergency decrees and the military’s loyalty equaled Congress’s constitutional levers. The constitution seemed balanced only because he was the counterweight.

This is precisely where the structural flaw emerges. When Fujimori fled the country in 2000, he took with him the military loyalty that had once neutralized Congress. The presidency weakened; Congress did not. Congress became the sole holder of legislative authority, with no Senate, no president strong enough to check its power. It could not only control legislation, but also force the resignation of the prime minister and the entire cabinet through a majority vote in which congress determines that it no longer trusts the President’s leadership or decisions, which legally obligates the cabinet to step down. Above all, the most consequential jurisdiction of the 1993 charter was the “permanent moral incapacity” clause. The line is as vague as it gets. There is no specification of how Congress determines that a president is morally incapable. Congress just needs a majority vote to authorize an impeachment. In the long term, this ambiguity produced a Congress that holds supreme authority over Peruvian politics. 130 legislators wield the constitutional power to depose a president whenever they judge it politically convenient.

2025 is a perfect illustration of the wreckage produced by the 1993 Constitution. For three years, until her removal this past October, President Dina Boluarte governed Peru with an approval rating so abysmally low that it broke every historical record: according to a 2025 Reuters report, as low as 2 percent, and consistently under 10 percent since 2024. As political analyst Francesca Emanuele explains in a CEPR article, the reason a president rejected by 98 percent of Peruvians remained in power for so long is because of a “self-serving Congress that ke[pt] her in power,” a “legislative body whose members oppo[sed] new elections that [would] threaten their power.” To call Congress self-serving is simply to say that it is indifferent to the public will. Even when an entire nation demands a president’s removal, Congress refuses to listen. Boluarte, then, was used as a tool that prevented congress from facing a presidential election, which would place every congressional seat at risk.

Boluarte’s unpopularity, moreover, strengthened Congress’s hand. A president with two to five percent approval has no political base, no party structure, no street support, and no leverage. She cannot resist congressional reforms, censure motions, or appointments. She must sign what Congress passes. Thus, she did. Boluarte approved the APCI Law, which—as documented by Human Rights Watch—forces NGOs and independent outlets receiving international funding to obtain approval from the Peruvian Agency for International Cooperation. Acting without approval can be deemed an illegal activity. In practice, this means that journalists, investigators, and human rights organizations cannot report on or investigate misconduct without the government’s blessing. The law is a shield against scrutiny, which is convenient for a Congress in which 80 of 130 members face corruption investigations. Boluarte merely held that shield; Congress wielded it. She remained useful until she did not. When public rage against Boluarte began to spill over into Congress’s own approval, legislators discarded her. They invoked the same “moral incapacity” clause born in the 1993 Constitution and replaced her with Congress’s own president—another demonstration of how in Peru, Congress, not the people, governs.

Congress’s supreme control over Peruvian politics represents the legacy of what happens when a strongman dismantles institutions rapidly, without regard for the future; when a president, confronted with crisis, knocks down the very foundations meant to constrain him. This is exactly what we are witnessing in the United States today. Trump’s campaign framed the country as collapsing—economically unstable and overrun by immigrants—and in need of immediate, extraordinary action. Once in office, he has used that narrative to justify a consolidation of executive authority. He has fired thousands of civil servants and hollowed out agencies responsible for regulatory oversight, like the Department of Labor and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. He has frozen or dismantled divisions tasked with environmental protection and civil rights enforcement—shutting down the EPA’s Environmental Justice office and freezing the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division. Further, he has purged inspectors general who monitor executive misconduct, removing the Defense Department’s Robert Storch and the Treasury’s Richard Delmar. These are not adjustments, nor are they the “reconstructions” like Fujimori once labeled his own modifications to the Peruvian government. They are structural amputations, which, although we do not yet know the full extent of the damage, we can refer to the lesson of Fujimori’s reign: when leaders tear down institutions to expand their own authority, the consequences outlive them.

AP News. “Peru’s Congress Approves New Law Regulating APCI.” Associated Press, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/peru-congress-new-law-regulating-apci-d74aba95afb55d03b5d6a6b8783cf0b3.

AEI (American Enterprise Institute). “Peru’s Constitutional Crisis Explained.” Washington, DC: AEI, n.d. https://www.aei.org/foreign-and-defense-policy/perus-constitutional-crisis-explained/.

BFI (Becker Friedman Institute). The Case of Peru. University of Chicago, n.d. https://manifold.bfi.uchicago.edu/read/the-case-of-peru/section/12466d4e-8123-4775-be11-3cc718678fcf.

Carranza, Panel Speakers. “Panel 6: Peru.” PDF, 2025. https://atticusvangundy.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/977ea-panel6perucarranza.pdf.

CCSDD (Center for Constitutional Studies and Democratic Development). “Constitutional Wars: Constitutional Roots of the Peruvian Political Crisis.” Bologna: CCSDD, n.d. https://www.ccsdd.org/BlogArticles/articleprofile/2-Constitutional-Wars-Constitutional-Roots-of-the-Peruvian-Political-Crisis.cfm.

CEPR (Center for Economic and Policy Research). “Peru’s Unpopular President Remains a Threat to Its People.” Washington, DC: CEPR, 2025. https://cepr.net/publications/perus-unpopular-president-remains-a-threat-to-its-people/.

CBPP (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities). “Trump Administration’s Mass Layoffs of Federal Workers Are Illegal.” Washington, DC: CBPP, 2025. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/trump-administrations-mass-layoffs-of-federal-workers-are-illegal.

ClinRegs. Peru: Constitution (Google Translation). U.S. National Institutes of Health. PDF. https://clinregs.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/peru/PeruConstitution_GoogleTranslation.pdf.

ConstitutionNet. “Back to Bicameralism for Illiberal Goals in Peru?” ConstitutionNet, n.d. https://constitutionnet.org/news/voices/back-bicameralism-illiberal-goals-peru.

Congress of Peru. Mensaje a la Nación, 1992. Lima: Congreso de la República del Perú. https://www.congreso.gob.pe/Docs/participacion/museo/congreso/files/mensajes/1981-2000/files/mensaje-1992-1-af.pdf.

DSM Forecast International. “Gridlock to Golpe: Can Peru Break the Cycle?” December 9, 2022. https://dsm.forecastinternational.com/2022/12/09/gridlock-to-golpe-can-peru-break-the-cycle/.

Federal News Network. “The Deposed Inspector General from the Biggest Department Speaks Out.” 2025. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/agency-oversight/2025/02/the-deposed-inspector-general-from-the-biggest-department-speaks-out/.

GWU – George Washington University. McClintock, Cynthia. “Why Fujimori Carried Out the 1992 Autogolpe.” Washington, DC: GWU, 2000. https://www2.gwu.edu/~clai/docs/McClintock_Cynthia_06-00.pdf.

Human Rights Watch. Congress in Cahoots: How Peru’s Legislature Is Allowing Organized Crime to Thrive. New York: HRW, July 8, 2025. https://www.hrw.org/report/2025/07/08/congress-in-cahoots-how-perus-legislature-is-allowing-organized-crime-to-thrive.

Human Rights Watch. “Peru: Amnesty Bill Signed into Law.” August 13, 2025. https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/08/13/peru-amnesty-bill-signed-into-law.

International Refugee Board of Canada. Peru: Country Report. Ottawa: IRB, 1994. https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/irbc/1994/en/21692.

Kellogg Institute for International Studies. Working Paper No. 161. Notre Dame: Kellogg Institute. https://kellogg.nd.edu/sites/default/files/old_files/documents/161_0.pdf.

Organization of American States. Einaudi, Luigi. The Situation in Peru, April 6, 1992. OAS Speech Archive. https://www.oas.org/en/columbus/docs/luigi-einaudi/SpeechesStatements92-93/The%20situation%20in%20Peru%204.6.92.pdf.

PCWCR (Princeton Case Studies in World Constitutions). “Peru 1993 Case Report.” Princeton University, n.d. https://pcwcr.princeton.edu/reports/peru1993.html.

Refworld. “Peru: Country Report.” UNHCR/IRBC, 1994. https://www.refworld.org/reference/countryrep/irbc/1994/en/21692.

UIC School of Law. “White Paper on Peru.” Chicago: University of Illinois Chicago School of Law. https://repository.law.uic.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=whitepapers.

UCLA International Institute. “Peru and Democracies in Crisis.” UCLA, n.d. https://international.ucla.edu/institute/article/19898.

Washington Post. “Environmental Justice Offices Thrown into Turmoil under Trump.” Washington Post, February 6, 2025. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2025/02/06/environmental-justice-offices-trump-turmoil/.

WOLA – Washington Office on Latin America. Peru: Deconstructing Democracy under Fujimori. Washington, DC: WOLA, n.d. https://www.wola.org/sites/default/files/downloadable/Andes/Peru/past/peru_deconstructing_democracy_fujimori_eng.pdf.